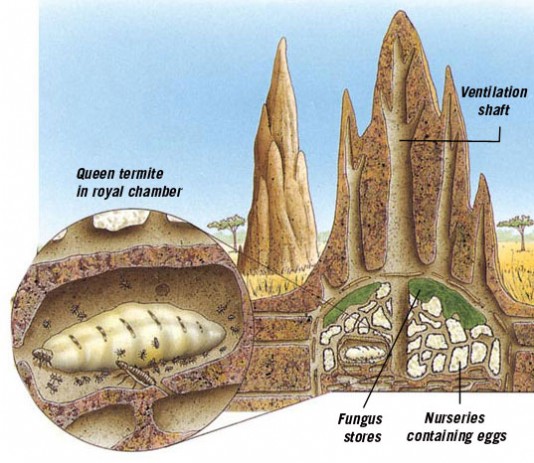

Beneath every termite mound lies a sprawling underground fortress made of interconnected chambers, tunnels and nurseries. While the exterior mound is designed for ventilation and climate control, the true heart of the colony is concealed safely below.

The Royal Chamber

At the center lies the royal chamber, a heavily protected room where the queen and king live. The chamber is usually surrounded by thick walls and guarded constantly by soldier termites. Only a few narrow passages connect it to the rest of the colony, making it one of the safest places in the subterranean nest.

The Queen’s Life

A termite queen is one of the most remarkable animals on Earth. After mating, her abdomen swells enormously – sometimes reaching the size of a human finger – in a process called physogastry. In this state, she becomes a specialized egg-laying machine and can produce thousands of eggs per day depending on the species.

She rarely, if ever, moves once physogastric. Worker termites feed her, groom her, and transport her eggs to the nursery chambers. The king remains with her throughout her life, continuing to fertilize eggs and supporting colony stability – a rare lifelong partnership in the insect world.

A queen can live 10–20 years or more, far longer than most insects. As she ages, the colony may raise replacement royals to ensure continuity.

Worker and Soldier Chambers

Surrounding the royal chamber are specialized rooms that support the colony’s castes:

Nursery chambers – warm, humid rooms where workers tend eggs and young larvae.

Fungus gardens (in Macrotermes and Odontotermes) – chambers where termites cultivate a symbiotic fungus used to break down tough plant fibers.

Food and waste chambers – used for storing partially processed plant material and isolating waste to maintain colony hygiene.

Soldier galleries – positioned near entrances for defense, allowing soldiers quick access to threats such as ants or predators.

A Perfectly Organized Society

Every chamber has a purpose. Workers constantly rebuild walls, expand tunnels, and adjust airflow. Soldiers defend. The queen lays eggs and produces chemical signals (pheromones) that keep the colony organized and functioning like a single super-organism.

Together, this hidden architecture and cooperative lifestyle make termite colonies some of the most complex societies in the natural world – and the towering mound above is just the surface hint of this extraordinary civilization.